Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Is there a Cartesian Circle?

How do I know that what I clearly and distinctly perceive is true?

1. God exists.

2. God is the ultimate source of these perceptions.

3. God does not deceive.

How do I know that God exists?

1. What I clearly and distinctly perceive is true.

2. I clearly and distinctly perceive that God exists.

‘[F]rom this contemplation of the true God ... I think I can see a way forward to the knowledge of other things. To begin with, I recognize that it is impossible that God should ever deceive me. . . . And since God does not wish to deceive me, he surely did not give me the kind of faculty which would ever enable me to go wrong while using it correctly’

Meditation IV

also: doubt about clear and distinct perception

(e.g. doubt that 2+3=5)

1. It is possible to doubt things that are clearly perceived.

2. We must find justification for removing doubt.

3. Therefore, we must find justification for not doubting what is clearly perceived.

‘what I took just now as a rule, namely that everything we conceive very clearly and very distinctly is true, is assured only for the reasons that God is or exists

, that he is a perfect being, and that everything in us comes from him. It follows that our ideas or notions, being real things and coming from God, cannot be anything but true, in every respect in which they are clear and distinct.’

Discourse on Method

‘I am certain that I am a thinking thing.

Do I not therefore also know what is required for my being certain about anything?

In this first item of knowledge there is simply a clear and distinct perception of what I am asserting; this would not be enough to make me certain of the truth of the matter if it could ever turn out that something which I perceived with such clarity and distinctness was false.’

‘I now seem to be able to lay it down as a general rule that

whatever I perceive clearly and distinctly is true’

Meditation III

God exists therefore clear perceptions are true

or

Clear perceptions are true therefore God exists?

‘I think I can see a way forward to the knowledge of other things ... since God does not wish to deceive me, he surely did not give me the kind of faculty which would ever enable me to go wrong while using it correctly’

Meditation IV

‘there arises in me a clear and distinct idea of a being who is independent and complete, that is, an idea of God.

And from the mere fact that there is such an idea within me [...] I clearly infer that God also exists [...]

So clear is this conclusion that I am confident that the human intellect cannot know anything that is more evident or more certain.’

Meditation VI

1. If we can know anything, then we can know God exists.

2. We can know something.

3. Therefore, we can know God exists.

4. But God doesn’t deceive us.

5. Therefore what we clearly perceive is true.

Two Interpretations

1. The sciences need a metaphysical foundation.

2. This foundation must include a refutation of scepticism.

‘I had seen many ancient writings by the Academics and Sceptics on this subject, and was reluctant to reheat and serve this precooked material’

Second Replies

1. The assumption that sensory perception enables us to know the essential nature of things leads to bad science.

2. Reflection on possible grounds for doubt provides reasons to reject this assumption.

If Descartes were refuting scepticism, the Cartesian Circle would be inescapable.

But it isn’t.

So Descartes isn’t refuting scepticism.

... or?

’an atheist can be clearly aware that the three angles of a triangle are equal to two right angles [...]. But I maintain that this awareness of his is not true knowledge, since no act of awareness that can be rendered doubtful seems fit to be called knowledge’

Second Replies

A Puzzle about the Senses

‘I have been in the habit of misusing the order of nature. For‘the proper purpose of [...] sensory perceptions [...] is simply to inform the mind of what is beneficial or harmful [...];

and to this extent they are sufficiently clear and distinct.

But I misuse them by treating them as reliable touchstones for immediate judgements about the essential nature of the bodies located outside us;

yet this is an area where they provide only very obscure information.’

Descartes, Meditation IV

Sensory perceptions of tastes, smells, sounds, heat, cold, light, colors and the like ‘do not represent anything located outside our thought’

These sensory perceptions ‘vary according to the different movements which pass from all parts of our body to the ... brain’

Principles

‘Something which I thought I was seeing with my eyes is in fact grasped solely by the faculty of judgement which is in my mind’

(Meditation 2).

Is Descartes’ consistent?

Sensory perceptions of tastes, smells, sounds, heat, cold, light, colors and the like ‘do not represent anything located outside our thought’

Principles

‘the proper purpose of [...] sensory perceptions [...] is simply to inform the mind of what is beneficial or harmful’

Sensory perceptions ‘normally tell us of the benefit or harm that external bodies may do [...], and do not, except [...]accidentally, show us what external bodies are like in themselves’

‘pain will be felt as if it were in the foot [...] deception of the senses is natural’

‘[the intellect] must not judge that external things always are just as they appear to be.’ (Rule 12)

Inconsistent tetrad:

1. Sensory perceptions represent things.

2. What can represent can misrepresent.

3. Anything that can misrepresent can be a source of error.

4. Sensory perceptions cannot be a source of error.

External bodies

‘may not exist in a way that

exactly corresponds with my sensory grasp of them,

for in many cases the

grasp of the senses

is very obscure and confused.

But at least they possess all the properties which I clearly and distinctly understand,

that is all those which, viewed in general terms, are comprised within the subject matter of pure mathematics.’

‘the intellect can never be deceived by any experience, provided that when the object is presented to it, it intuits it in a fashion exactly corresponding to the way in which it possesses the object, either within itself or in the imagination.

‘[the intellect] must not judge that external things always are just as they appear to be.’

In all such cases we are liable to go wrong, as we do for example when we take as gospel truth a story which someone has told us;

‘... the the wise man will not judge that whatever comes to him from his imagination ... passes, complete and unaltered, from the external world to his senses, and from his senses to the corporeal imagination’

Rules for the Direction of the Mind, Rule 12

1. On Descartes’ view, do the senses represent things?

2. If so, how is it that the senses never misrepresent things? (Or, if they do sometimes misrepresent, why are they not a source of error)?

3. If not, why must we ‘not judge that external things always are just as they appear to be’?

A resolution?

‘consider the reasons why [vision] sometimes deceives us.

‘those ... who are looking through yellow glass ... attribute this colour to all the bodies they look at’

Optics

Sensory perceptions of tastes,smells, sounds, heat, cold, light, colors and the like ‘do not represent anything located outside our thought’

Principles

Descartes’ big insights

1. The intellect is independent of sensory perceptions: it does not have to accept the principles implicit in perceptual processes.

2. We can explain why perceptual processes implicitly rely on principles which sometimes yield misrepresentations by appeal to the proper purpose of sensory perception.

Conclusion

Why doubt?

... to refute scepticism?

Doubt is necessary to establish ‘anything at all in the sciences that is stable and likely to last’

‘although I feel heat when I go near a fire and feel pain when I go too near, there is no convincing argument for supposing that there is something in the fire which resembles the heat, any more than for supposing that there is something which resembles the pain.

There is simply reason to suppose that there is something in the fire, whatever it may eventually turn out to be, which produces in us the feelings of heat or pain’

Meditation VI

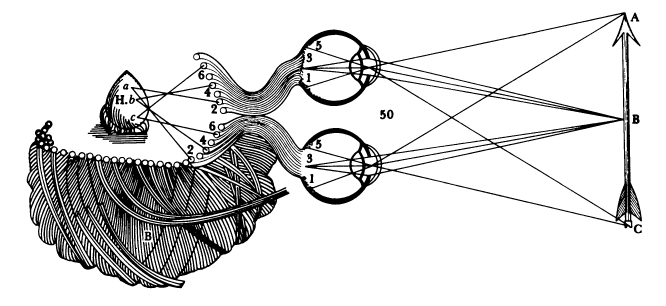

Treatise on Man figure 1

Treatise on Man, figure 2

Why doubt?

Not to refute scepticism.

But because doubt is ‘the easiest route by which the mind may be led away from the senses’.

‘... the principal reason for doubt, namely my inability to distinguish between being asleep and being awake. For I now notice that there is a vast difference between the two, in that dreams are never linked by memory with all the other actions of life as waking experiences are.’

Meditation VI

... or?

‘I wanted to show the firmness of the truths which I propound later on, in the light of the fact that they cannot be shaken by these metaphysical doubts. ...

I could not have left them out, any more than a medical writer can leave out the description of a disease when he wants to explain how it can be cured.’

Third Replies

conclusion

Why doubt?

Even at the end,

the reasons Descartes gives for doubting

remain a mystery.