Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

does not represent anything

a bruise

a meteor crater

an antique gold coin

an electric shock

does represent something

a tatoo of your Mum

an inscription

a treasure map

a thought about electricity

Do sensory perceptions represent anything?

Sensory perceptions of tastes, smells, sounds, heat, cold, light, colors and the like ‘do not represent anything located outside our thought’

These sensory perceptions ‘vary according to the different movements which pass from all parts of our body to the ... brain’

Principles

‘Something which I thought I was seeing with my eyes is in fact grasped solely by the faculty of judgement which is in my mind’

(Meditation 2).

What about appearances?

(Partially immersed stick appearing bent, e.g.)

How can things appear to be other than they are?

-- Sensory perceptions can misrepresent them.

‘when I see a stick, it [is] simply that rays of light are reflected off the stick and set up certain movements in the optic nerve and, via the optic nerve, in the brain

This movement in the brain ... is the first grade of sensory response.

the second grade ... extends to the mere perception of the colour and light reflected from the stick [...]

Nothing more than this should be referred to the sensory faculty, if we wish to distinguish it carefully from the intellect.

But suppose that ... I make a rational calculation about the ... shape ... of the stick:

although such reasoning is commonly assigned to the senses (which is why I have here referred it to the third grade of sensory response), it ... depends solely on the intellect.

Sixth Replies

What about appearances?

(Partially immersed stick appearing bent, e.g.)

How can things appear to be other than they are?

-- Sensory perceptions can misrepresent them.

-- They cannot. There are no incorrect appearances.

Does reflection on appearances show that sensory perceptions must represent things outside our thought?

philosophical

methods

informal observation,

guesswork (‘intuition’),

reasoning,

& theoretical elegance

‘any given movement occurring in the part of the brain that immediately affects the mind produces just one sensation in it;

Sixth Meditation

Does reflection on appearances show that sensory perceptions represent things outside our thought?

If so, is Descartes wrong about error?

The intellect is the faculty of representation.

The will is what affirms or denies something represented

Judgement occurs when the intellect represents something which the will affirms (or denies).

Error occurs when the will affirms (or deines) incorrectly.

a complication

‘[the intellect] must not judge that external things always are just as they appear to be.’

Rules for the Direction of the Mind, Rule 12

Refuted by Science?

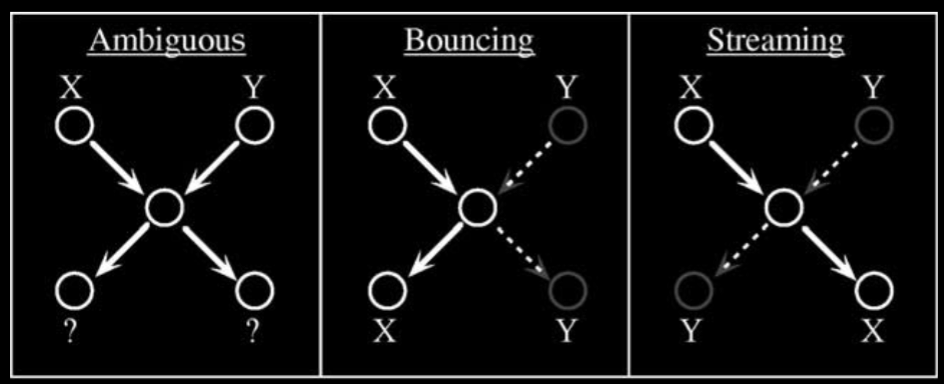

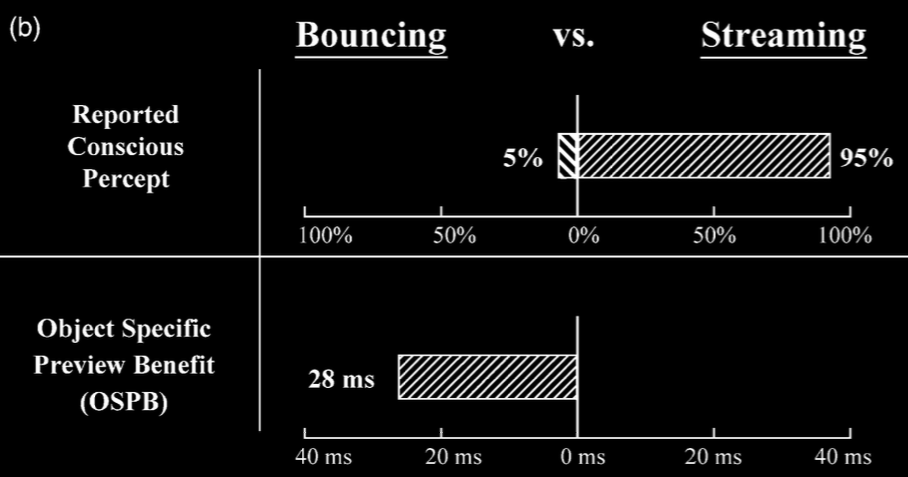

Mitroff, Scholl and Wynn 2005, figure 2

Mitroff, Scholl and Wynn 2005, figure 3

[video]

Mitroff, Scholl and Wynn 2005

Mitroff, Scholl and Wynn 2005

Descartes: The will is the sole source of error.

Steve: What about sensory perceptions?

Descartes: Sensory perceptions do not represent.*

Steve: That’s untrue because sensory perceptions can conflict with judgements.

also representational momentum ...

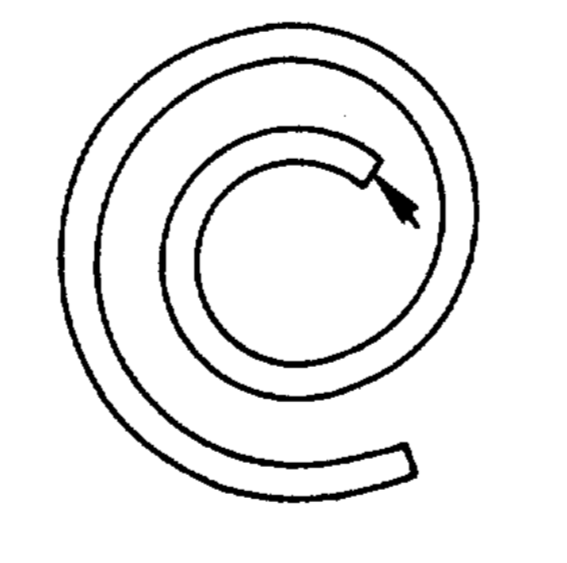

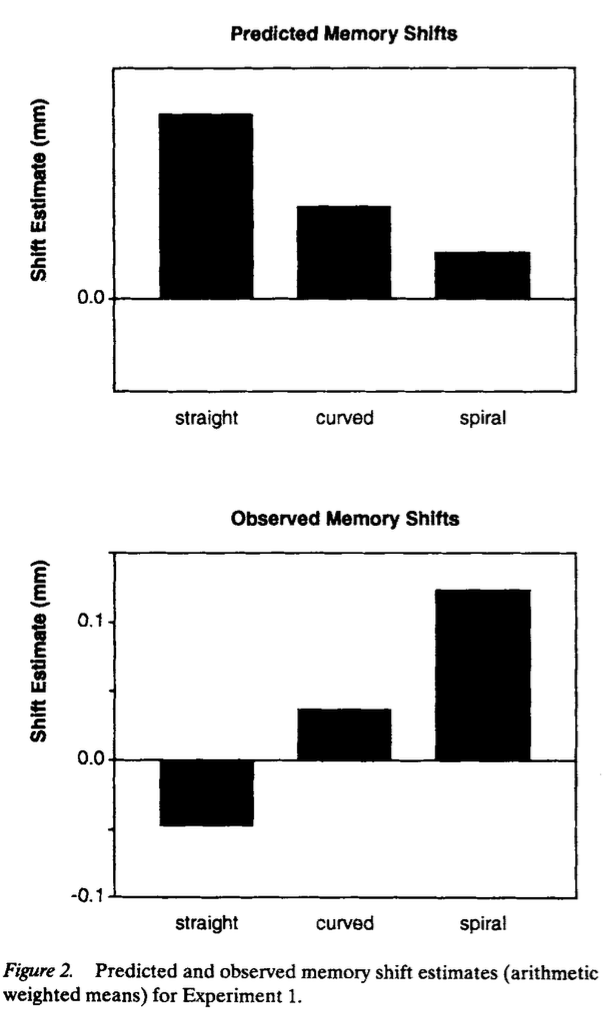

Freyd & Jones, 1994 figure 2

Yet ‘our subjects had relatively accurate conscious knowledge of the trajectory of a ball exiting a spiral tube (63% to 83% chose the correct path; only 4% chose the spiral path).’

‘subjects showed a memory shift for a path that the majority of subjects did not consciously consider correct’

Descartes: The will is the sole source of error.

Steve: What about sensory perceptions?

Descartes: Sensory perceptions do not represent.*

Steve: That’s untrue because sensory perceptions can conflict with judgements.

Or?

Descartes: The will is the sole source of error.

Steve: What about sensory perceptions?

Descartes: Sensory perceptions do not represent.*

Steve: That’s untrue because sensory perceptions can conflict with judgements.

conclusion

- The intellect is the sole source of error

- Thf. the senses do not represent

- Thf. there are no perceptual appearances ... and no representational momentum

Part 2