Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

McCloskey et al, 1980 figure 1 (part)

How can we acquire knowledge about the essential nature of the bodies located outside us?

Each body has a form, which is its essential nature.

When a body is perceived, its form thereby enters the mind.

When a body is perceived, your sensory perception resembles the body’s form.

Thanks to this resemblance, your sensory perception acquaints you with the forms (essential natures) of bodies.

not

Descartes’ view

‘I have been in the habit of misusing the order of nature. For‘the proper purpose of [...] sensory perceptions [...] is simply to inform the mind of what is beneficial or harmful [...];

and to this extent they are sufficiently clear and distinct.

But I misuse them by treating them as reliable touchstones for immediate judgements about the essential nature of the bodies located outside us;

yet this is an area where they provide only very obscure information.’

Descartes, Meditation IV

How can we acquire knowledge about the essential nature of the bodies located outside us?

Each body has a form, which is its essential nature.

When a body is perceived, its form thereby enters the mind.

When a body is perceived, your sensory perception resembles the body’s form.

Thanks to this resemblance, your sensory perception acquaints you with the forms (essential natures) of bodies.

How can we acquire knowledge about the essential nature of the bodies located outside us?

Sensory perceptions provide only very obscure information about the essential nature of bodies.

∴ Not by treating sensory perceptions as a basis for judgements about them.

The Obscurity of Sensory Perceptions

How can we acquire knowledge about the essential nature of the bodies located outside us?

Sensory perceptions provide only very obscure information about the essential nature of bodies.

∴ Not by treating sensory perceptions as a basis for judgements about them.

McCloskey et al, 1980 figure 1 (part)

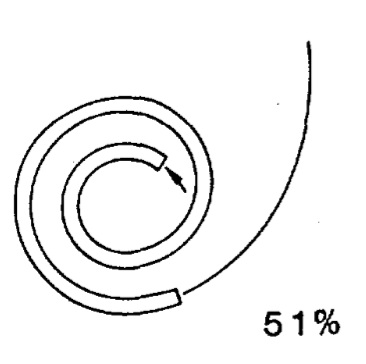

McCloskey et al, 1980 figure 2D

The person who sets the ball moving impresses in it a certain impetus, [which acts] in the direction toward which the mover was moving the body, either up or down, or laterally, or circularly’ (Buridan, 13xx; cited by McCloskey et al).

But what does this tell us about sensory perceptions?

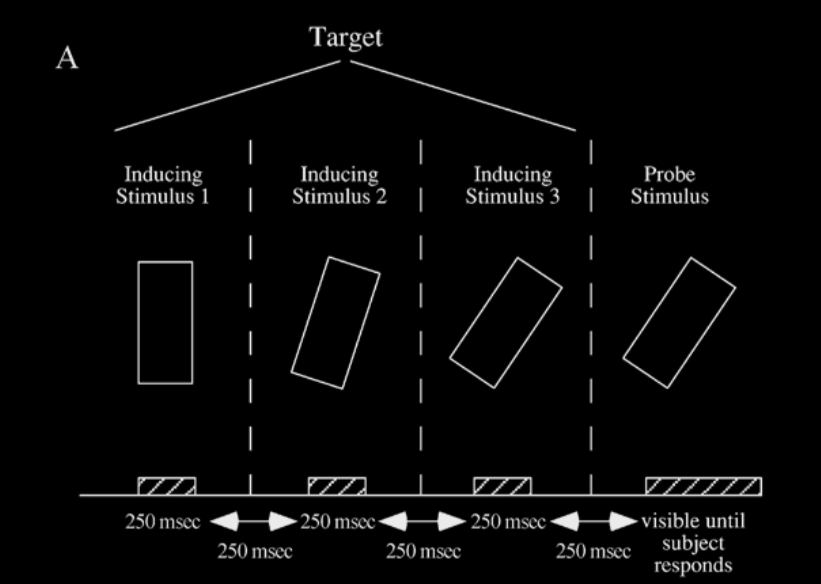

representational momentum

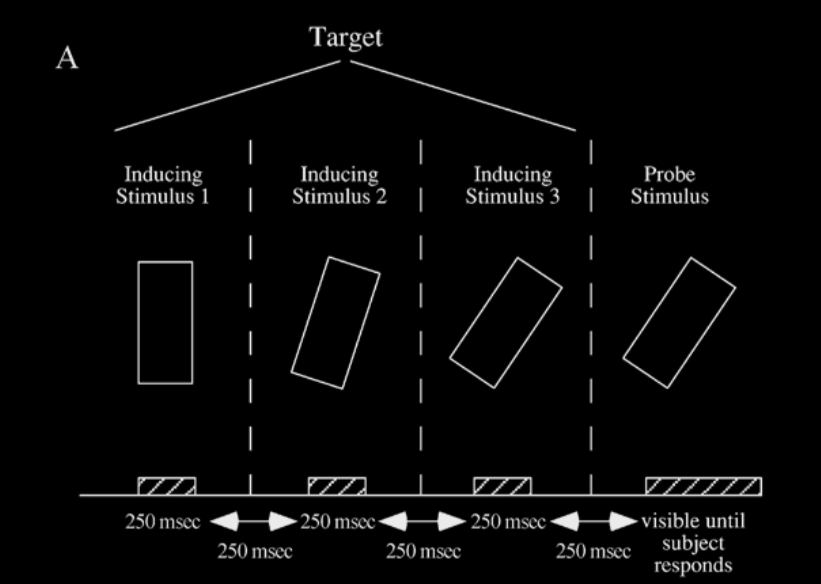

Hubbard 2005, figure 1a; redrawn from Freyd and Finke 1984, figure 1

Hubbard 2005, figure 1b; drawn from Freyd and Finke 1984, table 1

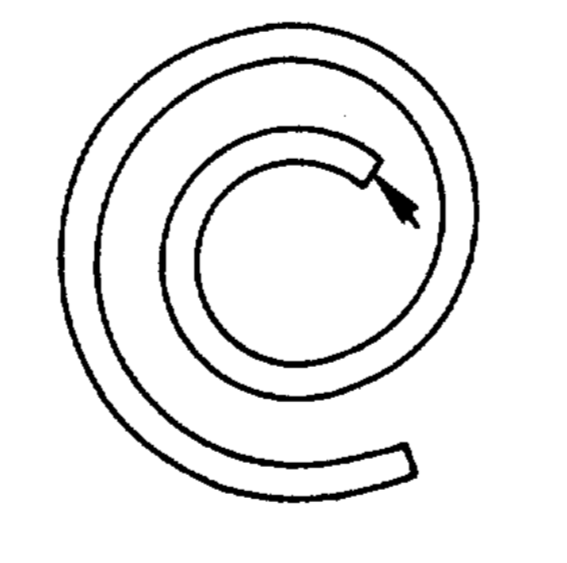

Freyd & Jones, 1994 figure 2

Yet ‘our subjects had relatively accurate conscious knowledge of the trajectory of a ball exiting a spiral tube (63% to 83% chose the correct path; only 4% chose the spiral path).’

‘subjects showed a memory shift for a path that the majority of subjects did not consciously consider correct’

‘the representational momentum memory shift for a ball following a spiral path after exiting a tube is greater than the memory shift for a ball following the physically correct linear path. A curvilinear path, midway between the spiral and straight paths, produces shifts midway between those for the other two paths’

Yet ‘our subjects had relatively accurate conscious knowledge of the trajectory of a ball exiting a spiral tube (63% to 83% chose the correct path; only 4% chose the spiral path).’

‘subjects showed a memory shift for a path that the majority of subjects did not consciously consider correct’

Freyd & Jones, 1994 p. 975

✓

How can we acquire knowledge about the essential nature of the bodies located outside us?

Sensory perceptions provide only very obscure information about the essential nature of bodies.

∴ Not by treating sensory perceptions as a basis for judgements about them.

one last thing

Aristotelian physics ‘is reasonably effective for organizing bodies of knowledge.

From the perspective of modern physical and biological science, however, it is severely crippled by its close linkage with what Wilfrid Sellars calls ‘the manifest image’, i.e. what is available to us by means of our very limited sense organs. [...]

The tie to entities known through perception prevents access to—much less the discoveries of—modern physics (and, consequently, chemistry and biology)’

Turnbull 1988, p. 120

Practicalities

books

Descartes’ Meditations (CUP)

Hatfield

web

seminar tasks

yyrama

assessment